Chapter

6 - Kerrigan’s Testimony

Kerrigan’s manner betrayed a great

deal of nervousness, whether the result of his long sojourn in jail or arising

from the position he found himself in. He was evidently anxious to screen

himself and at the same time seemed to wish to damage the case of the

prisoners. His testimony was very important in its corroboration of McParland,

and undoubtedly did damage the case of the defense. Kerrigan interlaced his

testimony at times rather copiously with profanity, and was rebuked by Judge

Pershing. His queer language caused a good deal of laughter. He was escorted to

and from jail by a large force of police, as a measure of precaution. He said,

in substance:

“I

live in Tamaqua; have lived there between six and seven years, as near as I can

think; I knew the defendants here, Hugh McGeehan, Thomas Duffy, James Boyle,

James Roarity, and James Carroll; I knew Benjamin F. Yost between nine and ten

months, I think; sometime in the Fall or Winter of 1874 (the Winter before Yost

was killed) I was present when a difficulty occurred between him and Thomas

Duffy. The first time I met Thomas Duffy at the corner between the United

States Hotel and the Columbia House, and Thomas Duffy called Yost a Dutch son

of a bitch. I was with him, and Yost said to me to take him away. Then Duffy

and I started off, and I did the best I could to take him away, but Duffy ran

around the Columbia House and came back again, and Yost said if I did not take

him away he would hurt him, so we got him away that night. Another night I was

taking Tom Pursell home, and he was tight. We got him home, and we were coming

down the street, and Duffy was with me, and then a fellow by the name of Flynn

was coming up from Frackville that way and he halloaed that he was “an Irish navigator,”

and Duffy ran after him, and Barney McCarron and Yost was there. Then we all

had some words, and so McCarron held me while Flynn was putting the knife to

me. Then he searched me to see if I had any weapons, but did not get none. Then

McCarron took Duffy to the lockup and then took me to Doctor Goulden that I

might get sewed up. I did not know the next morning that Duffy was beat, or

anything. I found that out by James Carroll, who came to my house.”

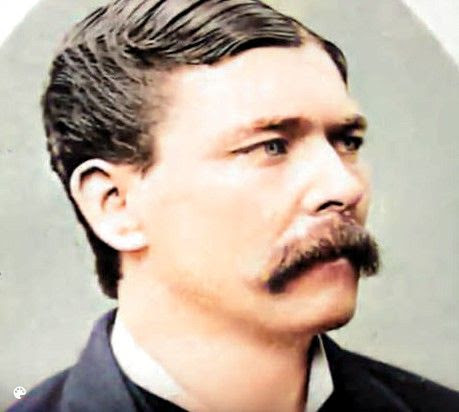

James Kerrigan after his release from Carbon County Prison

“The

next place I saw Duffy was in Squire Lebo’s office. He said: “Never mind; for

what we have suffered we will make Yost’s head softer than his ass.” He showed

me his forehead, where Yost had hit him; he had a large plaster on his head

where he was beat. He said that Yost had done it. At another time he told me,

down in Tom Carroll’s, that he had a notion to go and shoot Yost himself, him

and Mickey Campbell, at the Run, and Jim Carroll said he had better leave it

alone as he was well known, and as Mickey did not belong to the organization,

it might not be safe to do it, and he said: “Never mind; we will pay a couple

of strangers to do it.” Thomas Duffy told me that in Jim Carroll’s house in the

presence of Carroll. This was somewhere about the first of June, 1875. I think

about the middle of June, I came down on the street, and, as I was going down

by the Columbia House, on Broad Street, in Tamaqua, I was going over past James

Carroll’s, and Thomas Duffy and James Roarity was standing on James Carroll’s

stoop, talking, - I mean Thomas Duffy and James Roarity, these prisoners. I

came up and the words I says was: “Well, blackguards, how are yez making it?”

That was just the words I said to them, and they said, “Good.” So I went on,

and I said: “What are yez stopping at now?” and Duffy then told Roarity he

would give him ten dollars to put Yost out of the road. “I will,” said Roarity,

“and you can bet on that, and if I do not do it myself, I will get two men that

will do it.” Then we went in there, and Duffy made the remark that he was

working a night shift, and he would send good men who would come and do the

work, and, he was going out, Duffy says: “Now you attend to that, and if I

don’t do it myself, I will get somebody that will do it.”

Well,

on the 5th of July last, I was in Tamaqua. The band was playing upon

the hill up where I lived, between 4 and 5 o’clock in the morning, and the

cannon was firing off, and I got up between4 and 5 o’clock and went down to

where the band was playing, and my two little boys was with me and I sat there,

and when the band was done playing, I went down town and sent the two little

boys home. I went down town before breakfast, and the two little fellows asked

me if I would not bring them up some shooting crackers and I said that when I

went down town, I would do it. So I went down town and staid around awhile, and

went about the street, and the first drink that I had that day was with George

Boyle and Barney McCarron; and I had it in the Columbia House. Me and Boyle was

standing by the Columbia House and Barney McCarron came along and we had a

drink. So from there I went over to James Carroll’s, and me and James Carroll

had another drink. I treated, and he treated, and from there I went up home. I

met a man named William Cresson. He was tight, and I went home and had

breakfast, and sat outside on the porch, with the two little fellows, showing

them how to fire off the shooting crackers. Then I laid down awhile on the

floor. I got up then, and I took a walk by the cemetery over to the picnic.

That was up toward Newkirk. I had a bit of a cane in my hand; I didn’t go into

the picnic ground, but I staid under the shade of the trees, and after that I

came away down again, and I met Roarity between the Columbia House and the

United States Hotel, and he says to me: “Where have you been all the morning?”

and I says, “I went down town early this morning, and went home and laid down,

and so,” says I, “let’s go down to Carroll’s, and we will have a drink.” “All

right,” says he, and we went down to Carroll’s and had a drink there. I think

that night between eleven and twelve o’clock, or one, I would not be positive

about the time, but it was somewhere about that neighborhood.

So

we had a drink. I treated, and he treated, and Jim Carroll treated, and Roarity

says to me: “Come over to Storm Hill.” “Oh no,” says I, “it’s too hot, and I

have got no money to spend to go over.” “Come to Campbell’s,” he says; “No, I

won’t” says I. And says he, “If you will come over to Storm Hill,” says he, “I

will be over tonight with you again.” Says I, “No, I have no money to spend.”

And then Carroll says, “Go on with him, and there is two dollars for you to

spend.” And he gave me the money. So I went on with Roarity, and we went to

Alexander Campbell’s, and when we got to Alexander Campbell’s there was some

other man in the bar-room; I can’t tell who it was. Roarity says, “Campbell,

did you see Hugh McGeehan and Mulhall here today?” “No,” says Campbell, “very

likely they’re in Chunk, or on the Hill.” Says Roarity: “I am going up to see

them.” Roarity started off and left me in Campbell’s and before he got back

there was word come to Aleck Campbell to tell Roarity that his wife was sick.

He was not there when the word was left. He came back and went home when he heard

it. That might be about 5 o’clock, or something like that – in the neighborhood

of it.

On

the road going to Storm Hill, Roarity told me that he had Tom Mulhall and Hugh

McGeehan to go and shoot Yost that night, and he was going to go along and show

them the road.

When

he got to Campbell’s he inquired from Campbell whether Tom Mulhall and Hugh McGeehan

had been there, and Campbell said they were not. After Campbell told him that

the men were not there he went to find them. When he came back he said to Campbell

that he had seen them on the Hill. Campbell gave him the word then, and he went

home, and I did not see him after that.

I

think it was about half past five or so when I left Campbell’s, and I reached

home about fifteen or twenty minutes after seven o’clock. Between 9 and 10

o’clock, I went down to Jim Carroll’s; Davy Davis and Owen James and some other

men were in the bar-room. I could not recognize who they were, but they were

sitting on the chairs, Davy Davis was drunk and Owen James was very drunk. They

had their glasses set on the bar, and they were drinking, and some other men

were sitting on the chairs, but I could not recognize who they were. The

bar-room in Carroll’s and the kitchen is on the one floor, and both doors face

one another; when there was nobody in the bar-room I used to go into the

kitchen, and I walked into the kitchen this night and the door was half closed.

Hugh McGeehan sat in the rocking chair in the kitchen and Thomas Duffy stood

beside him and James Carroll and James Boyle were there, and I went in; I said:

“How are you making out,” and they answered me: “All right;” and James Carroll

got up and walked out. Then we all got up and walked out on the stoop, and they

sat down; and Davy Davis was there when I passed out. We went on the stoop, and

Jim Carroll came up to the stoop from the direction of Herron’s saloon and said

he: “I can’t get none.” He said it to James Boyle and Hugh McGeehan and Thomas

Duffy, and I was present there. He sat down on the stoop, put his hand into his

vest pocket, took a quarter and says to me, “Jimmy, go over to Patrick Nolan’s

and say that you want the loan of his pistol for a man that has to go over to

Mauch Chunk. I went over to Nolan’s, and there was no one in Nolan’s but a man

named Patrick Coleman, and Nolan and his wife. I called Nolan to one side, and

asked him if he could loan me his revolver to give to a man who was going to

Mauch Chunk or Summit Hill, and he said that he had none, for he had loaned his

away. I came out from where I had called him aside and spent the quarter. I

took beer and Coleman took something out of a bottle, whether whiskey or not, I

do not know, and Nolan took a drink with me.

I

came back to them again at Carroll’s, and told them I could not get any from

Nolan; that he had none.

I

says to them: “What are you going to do?” Duffy made some remark about they

were going to get Yost “put out of the road.” I said to them: “You had better

leave that alone. Now drop it. I might be blamed for that, for Barney McCarron

and me had a fuss sometime before, and I think you had better drop that, or I

will get blamed for it.” With that Hugh McGeehan and Boyle got up, and whether

it was Boyle or Hugh McGeehan who said it, I could not say, but one of them

said: “By their God, they come three times to Tamaqua to do the job and they

were disappointed and by their God, they would not go home that night until

they did do it.” Them was the words.

So,

then, James Carroll, when he said these words, was making for the bar-room

door, and then all got up and they went in. McGeehan says: “I am all right, I

have got a five shooter; I have got Roarity’s pistol.” I saw it in his hand; I

knowed the pistol. Then we all went into the bar-room, and James Carroll went

behind his bar, and he pulled out a drawer that he had there for putting his

scraps in, or whatever it is, and pulled out a single barreled pistol, a breech

loader; and he made the remark that he only had one ball. I seen him put the

ball into the pistol, and he loaded it and gave it to Boyle, and Boyle put it

in his pocket; and he made the remark to Boyle; “It is a poor thing to do a job

like that with; if I had a good blackjack I would give it to you along with it.

Then they allowed that Roarity could not come along, that he had to stay home

because his wife was sick, and that Campbell told them that Carroll should get

somebody to show them the road. McGeehan said that they wanted to know the old

Mauch Chunk road, for they wanted to go that way after they would do it. So

Carroll said he did not know who would show them the road except me, for he

said that Duffy would have to stay there all night, so that he and his wife

could swear that Duffy knew nothing about it. Says I: “If I go with them to

show them the road I will be blamed for it.” Says Carroll: “It will be late,

and nobody will know.” I said I did not care. I would show them the road after

they would shoot him. Duffy took them up the railroad up by the depot, up by

the back way to the head of town, and left them at the cemetery. I told them I

would meet them at the cemetery, and after that I went up to the Columbia

House, and left them there. I stood at the Columbia House and looked into the

windows, and there was nobody in the bar-room, and, after that, I went up to

the Broadway House, kept by Michaels. There I went in, and Barney McCarron was

in there, and a large crowd. I had a drink with McCarron. He was treating, and,

after we drank, Frank Yost came in from the back room; I was treating and I

said: “Frank, take something?” He took a cigar on my treat, and I believe

Barney McCarron took another.

From

there I turned down to the corner of Gas Jake’s, and from there I went down by

Allen’s shop, and from there I went till my own house; and my woman asked me

what time it was. It was going to 1 o’clock exactly. From there I got a bottle

of whisky that was in my home, and went back across the hill and over to the

cemetery and met Boyle and McGeehan. They were standing at the cemetery, where

I told them I would meet them. We sat there a while talking and waiting for

them to come and put the lights out, and while we were waiting for them to come

and put the lights out, we seen them coming and they put the lights out down

the road first.

I

could see Yost and Barney McCarron, and when we seen them coming up at that

distance we walked down a piece toward the lamp with McGeehan and Boyle, and I

stood in there between sixty and seventy yards, as near as I can think, where

Roland Jones used to keep a store.

McGeehan

and Boyle went down to the lamp post. Barney McCarron stood across the railroad

a piece, and Yost crossed over to Lehigh Street to put the light out there

first, and came back. They went away some place else, I could not say where,

and did not put out this light for some time; and McGeehan and Boyle stood in

the shade of the trees waiting for them. They were there waiting some time, I

could not say how long, and then Yost and McCarron came out, and McCarron stood

at the corner of Squire Lebo’s house, across the railroad, and Yost went over

to put the light out, and got up on the ladder, and McGeehan had to reach up

and I seen him shoot him. He put his hand up and I seen the flash of the

pistol, and they were just like you were doing, like this (clapping his hands

twice, one after the other) that Boyle and McGeehan both shot at him.

They

might be within two yards of him when they fired. I might be within sixty or

seventy yards on the upper side of the street, looking right across. Yost did

not put out the light at all; the light burned. After they fired, Barney

McCarron fired two shots, to the best of my knowledge, across the railroad

after them. Then they ran to where I was and McGeehan fired another shot. He

thought Barney McCarron was after him. McGeehan said “The buggar was done now,”

and fired one shot. There was nobody else to fire, Boyle only had a one barrel

pistol, and he had fired it, and I had no pistol.

We

ran up the road going to Newkirk. We ran across the railroad, and up by the

spring where I was arrested. Down by Orwigsburg Street, down by the shaft, and

I was running, and as the morning was quite dark, I fell down the big ash bank

at the shaft, and tore the whole knee out of my pants. I have the pants down in

the Mauch Chunk prison, and you can see them now. I went on then, and left them

by the bridge, crossing the railroad by the shaft, and told them to go on down,

and I left them down by Manus Boyle’s, and I told them to go on until they met

a finger board and the first road they met beyond that they should turn off to

the left hand, going towards Centreville. That would take them out to the White

Bear.

I

came home, and got up to the door and got up on the porch, and pulled off my

boots so that nobody would hear me, and I hid my pants under the banisters,

under some clothes so that my wife would not see them. The door was not locked;

I did not lock the door from the time I had been there before. My wife had went

to bed” (Miner’s Journal).

Here is verbatim testimony from the

trial: Q. Did you ever have any

conversation with Boyle as to what he had done the next day after the shooting?

A. I had about the 14th or 15th of July. I had a

conversation with him, Alex Campbell and James Roarity in Storm Hill one Sunday

(the 14th and 15th of July in 1875, do not fall on a

Sunday). Q. What did he say? A. Boyle stated that he was sick that day, but he

started in the morning to go to work, and he had to quit work and he came home,

and when he got home, his wife (Boyle was never married) had a bottle of grog for him. He said he did

not work that day, but he went to work in the morning to make everything sure.

(West, page 74).

There are two, main inconsistencies,

that anyone can see, between the statement used for the prima facie case,

wherein, Kerrigan testifies that he was not present at the scene of the crime,

but had learned of its development from the defendants. Yet, during the trial,

Kerrigan has a long dissertation of his involvement and presence at the scene

of the homicide. Secondarily, Kerrigan maintains that Boyle was married, when

in fact, he was not.