Chapter

19 - Anti-Monopoly Convention

About

the 4th of March, 1875, an Anti-Monopoly Convention was appointed

to take place at Harrisburg, having for its principal purpose a movement

against the Philadelphia and Reading Coal and Iron Company, by individual and

other large operators. Among

them was Muff Lawler, who reported, on his return, that there were nearly three

hundred representatives present, and it was decided to ask the Legislature, by

resolution, to cause an investigation to be made, by committee, of the officers

of the Philadelphia and Reading Coal and Iron Company, and say why their charter should not be rescinded.

Proceedings at Harrisburg Yesterday –

Speeches and Resolutions – New York Times

Harrisburg, PA, March 3 – The

Anti-Monopoly Convention contains representatives from all the labor

organizations in New York and Pennsylvania, including the Grangers and retail

coal dealers. An address was read by Horace H. Day, of New York, representing

the Industrial Congress of the United States, who received a vote of thanks.

E.M. Davis, of Philadelphia, also delivered an address on the moneyed power of

the country, and its tendency to foster monopolies. The Convention adopted

resolutions condemning the passage by the Legislature of any bill which will

not hold the employer responsible for the competency of the apprentice when he

becomes a master mechanic, urging the passage of some law which will restrain

the large corporations from charging excessive rates of transportation,

condemning the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad Company for discharging those

of its employees who are members of corporate labor organizations, and

recommending the enactment of a law by the Legislature appointing a commission

to examine into the causes of the difficulties existing between labor and

capital, which shall report the testimony taken and the conclusion arrived at

to the Legislature at the next session.

The Convention reassembled this

afternoon at 2 o’clock in Barr’s Hall, President John F. Walsh, of Schuylkill

County, in the chair. A number of resolutions were adopted tending to oppose

monopoly, among them the following:

Resolved, That the action of the

Philadelphia and Reading Railroad Company in procuring by fraud and deception

the charter known originally as the Laurel Run Improvement Company, and now

called the Philadelphia and Reading Coal and Iron Company, whereby special

privileges of great value to them and danger to the community were granted, and

their abuse of said privileges, demand immediate attention. Upon the

Legislature of the State we urge the appointment of a joint committee of both

Houses to investigate the affairs of both corporations with instructions to

report an act repealing all or so much of their charters as may be detrimental

or dangerous to the public welfare.

A discussion of one hour took place

on the subject of uniting the laboring classes of the United States. Senator

Staunton, of Luzerne, addressed the convention on a bill before the Legislature

in the interests of the miners and laborers in the coal fields.

An evening session was held for the

further discussion of the question of uniting the mechanics, miners, and

laboring men of the country. Several delegates from New York addressed the

convention.

James McParland

Report March 11, 1875

The operative remarks today, that the

miners seem to have a great deal of determination and say they will not succumb

to the Reading Rail Road Co., under any circumstances. The operative made some

quiet inquiry among the Molly Maguires today, in regard to the affairs at

Ashton and learned that the Molly Maguires are very numerous in that section.

Thomas Fisher of Summit Hill is County Delegate for Carbon County and Pat McKenna

of Storm Hill is the Bodymaster, and it is generally thought by the Molly

Maguires of Shenandoah City, that the parties who created the disturbance at

Ashton, are not only Molly Maguires, but was more belonging to the various

secret organizations.

The

Legislature of Pennsylvania, listening to the repeated demands of the Anti-Monopoly Convention, appointed a committee to investigate the affairs of the

Philadelphia and Reading Company. That commission convened and heard testimony as the complainants could bring before it, as well as the pleadings

of the attorneys for the Philadelphia and Reading Company. Mr. Gowen,

the President of the Philadelphia and Reading Railway Company, personally

appeared before the committee and made answer to the charges.

It

was the sixth of July that the committee was in Pottsville. Franklin Gowen alluded to

troubles in the coal region: “It will not do to say that these troubles result

from the inadequacy of the price paid for labor, because, without exception,

the rates paid are the highest in the world. The high rates have had the effect

of attracting to the coal region a surplus of labor, more than sufficient to do

the work required; and it is the effort of this surplus to receive an

employment which it cannot really get that has led to all these disturbances. I have

had printed for your use a statement, from the daily reports coming to me

during the strike, of the outrages in the coal region. Here I want to correct

an impression that goes out to the public, that these outrages are intended to

injure the property of the employer. They are not. We do not believe that they

are. They are perpetrated for no other purpose than to intimidate the

workingmen themselves and to prevent them from going to work. I shall not read

the list; it is at your service; and you can look over it and see the position

we have occupied for months. But let me mention a few of the glaring instances

of tyranny and oppression. At a colliery, called the Ben Franklin Colliery, the

employees of which were perfectly satisfied with their wages, had accepted the

reduction early in the season, and were working peacefully and contentedly, the

torch of the incendiary was applied to the breaker at night. These men, having

families to support, working there contentedly and peacefully, were driven out

of employment by a few dangerous men, simply for the purpose of preventing them

from earning their daily bread. I had some interest in the subject of the

amount of their wages, and I asked the owner of the colliery what his miners

were actually earning at the time when they were prevented from working by the

burning of the structure in which they were employed, and he told me that the

lowest miner on his pay-list earned sixty dollars a month, and the highest one

hundred and thirty dollars; and yet, although these men were peaceful,

law-abiding men, they were driven out of employment by an incendiary fire. At

another colliery, within five or six miles of this, a band of twenty or thirty

men, in the evening – almost in broad daylight – went to the breaker, and by

force drove the men away and burnt the structure down. It belonged to a poor

man. It was a small operation. The savings of his lifetime were probably gone,

and his own employees, who had nothing against him, and who were perfectly

willing to work, were thrown out of employment, and probably remain out of employment

to this day.”

When Franklin Gowen concluded, the committee made its report, showing that there was no

ground of action, and that was the last heard of Legislative investigating the Company. In the meantime, Gowen pressed McParland to investigate and report on the officers and members of the Ancient Order of Hibernians, believing that they were the same as the Molly Maguires.

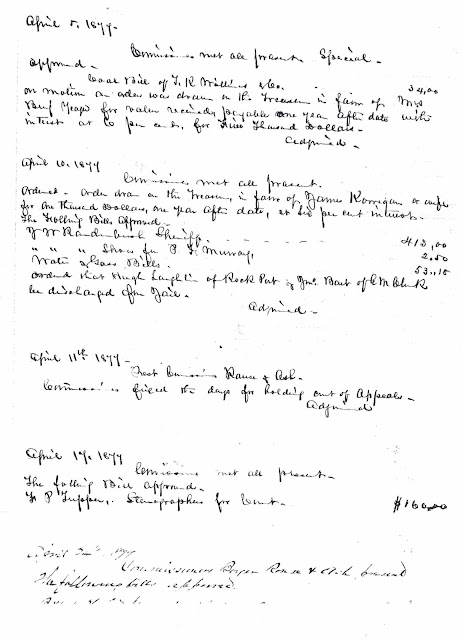

James McParland Report July 8, 1875

Operative J. Mc.F. reports that the

Molly Maguires appear to take but little interest in the investigating

committee. There are men in Pottsville from all parts of the County, and they

all agree in saying that it is impossible for an Irishman to get a job at

present.

James McParland Report July 9, 1875

The Molly Maguires declare that the

investigation was a humbug and say there was nothing in it. They all complain

of hard times. At 11AM the investigating committee left Pottsville.

James McParland Report July 20, 1875

Austin Maley, the Borough Constable,

this morning informed the operative, that Charles Haase wanted him, the

operative, to try and get bail for him by next Thursday, if possible. He said

the operative was the only man in the crowd who had any brains and he thought

he could get bail for him if he tried. Operative J.Mc.F. mentioned the subject

to McAndrews and Morris, the former said he thought he could get the bail.

James McParland Report July 21, 1875

The operative had a talk with John

Kehoe, County Delegate of Girardville today, he reports everything quiet in his

County. Kehoe asked Reilly to go bail for Charles Haase. Reilly said he would,

if he could be accepted. Kehoe then requested operative J.Mc.F. to go to

Pottsville tomorrow, and take Reilly with him and see if they could get Haase

out. Kehoe stands bail for some six or seven men, amounting in the aggregate to

some $10,000. He does not own a foot of real estate.

James McParland Report July 22, 1875

This morning Reilly told the

operative that he could not possibly go to Pottsville today, as there was a

liquor merchant in town, and he must remain and see him. He said he would

willingly give bail for Haase if he could, but as he was not worth $1,000, he

did not think there was any use in trying. The operative thought it would be a

good plan to see Haase, as perhaps he might be able to gain some important

information by him. Therefore he went to Pottsville and had an interview with

him in the jail. He told Haase that he had done all in his power to obtain bail

for him but had not yet succeeded; this made the prisoner feel very blue. He

talked freely with the operative, but did not appear to know anything in

particular of the doings of the Molly Maguires. After the operative’s return to

Shenandoah, he was told by McAndrews that he would see Colihan, of Gilberton

tomorrow, and see if he could obtain bail of him.

Charles Haase

Charles

Haase, who was just from Summit (Hill), where he had gone to secure work and

see some relatives, reported that the Laborer’s Union and the Mollies had made

common cause in the fight on Summit Hill, headed by Tom Fisher, County

Delegate, Pat McKenna, Bodymaster (of Storm Hill), and a prominent Mollie named

(Daniel) Boyle, (Bodymaster of Summit Hill). They were determined that, unless

the collieries submitted to the general demand, they should not have men to do

their work. Now, McParland had testimony to link the officers of the AOH to the troubles of the Labor Union. McParland ascertained the names of some of the officers and members of the AOH, but did not know the first name of the Bodymaster of Summit Hill. McParland just knew the last name of Boyle.

James McParland Report July 24, 1875

McAndrews and Reilly went to

Gilberton yesterday, but failed to obtain the bail, as Colihan said he was not

able to be bondsman for $1,000.